Lesson 2 Rapid Development in China and India

Image: Adam Schultz/Official White House Photo/Flickr.

Some analysts suggest that the post-crisis strategic reality — India's increased militarisation of the LAC and an inter-theatre rebalancing of forces — should be welcomed as a rational response to its threat environment. Indeed, a tangible response to the rapidly growing China threat is overdue — planning against Pakistan still attracts a disproportionate share of Indian military resources. Even with the Army's rebalance, 22 divisions still face Pakistan, while only 14 face China (and 2 are held in a national reserve).[51] In recent decades, the military's mid- and senior-grade officers grew to recognise China as India's most capable rival, but nevertheless harboured much greater emotive enmity towards Pakistan as India's primary threat.[52] In that context, the Ladakh crisis is a necessary catalyst to promote strategic adaptation, to focus more on the China threat.

But the manner of that adaptation risks leaving India in a worse position in its long-term strategic competition with China. Most significantly, it will probably defer much-needed military expansion in the Indian Ocean. Meanwhile, the increased militarisation of the LAC will not impose any significant material or political cost on China. This unequal distribution of costs is already generating a deeper crisis in Indian defence policy that will fester long after the current crisis in Ladakh.

India will defer overdue modernisation and maritime expansion

The central risk of India's new strategic reality is that it will reinforce India's traditional emphasis on its continental threats at the expense of addressing increasingly acute modernisation needs and maritime risks. India's military threat perceptions have always been dominated by the prospect of invasion or infiltration from Pakistan and China. This preoccupation with India's land borders accounts for the Army's domination of Indian defence budget allocations and its relatively slow expansion of maritime power in the Indian Ocean region.[53]

In recent years, India has taken tentative steps in modernising its military and expanding its maritime power in the Indian Ocean region. The Navy began to operate round-the-clock "mission-based deployments" at the ocean's key chokepoints, to monitor threats and respond quickly when needed.[54] It undertook a flurry of exercises with partners and, more importantly, operational activity, especially in providing humanitarian assistance and disaster relief, to expand its visibility and influence in the region.[55] And it started to acquire a slew of state-of-the-art platforms, including P-8I anti-submarine warfare and maritime patrol aircraft, MH-60R maritime multi-mission helicopters, and Sea Guardian drones — all of which would vastly improve its ability to operate in the ocean and cooperate with partner countries such as the United States and Australia.[56] Even the Air Force deployed its front-line Su-30MKI aircraft, armed with anti-ship BrahMos missiles, to southern India to operate over the Indian Ocean in 2020.[57] The trend was fledgling, but unmistakable.

Image: MCSN Drace Wilson/US Navy.

After Ladakh, the military is likely to slow down that modernisation and maritime expansion.[58] The LAC commands far greater political attention than distant corners of the Indian Ocean, even though the strategic challenge is more acute in the Indian Ocean. The China border is now the site not only of a menacing foreign army, but also foreign encampment on previously Indian-controlled territory, and the site of clashes that spilled Indian blood. The Indian Ocean, meanwhile, is a large and amorphous region of hypothetical future threats — certainly not the stuff that stokes politically-useful nationalist fervour. But it presents serious challenges to Indian policy. Given budgetary constraints, the resources to manage the new LAC threat must be found from somewhere within the military's current allocation. The risk is not that already-allocated resources will be diverted from the Navy to the Army — India cannot, for instance, re-task a guided-missile destroyer to the Himalayas. Rather, the risk is that future resource allocations will continue to favour the ground and supporting air forces slated for the military's highest-priority continental contingencies, at the expense of naval and supporting air forces that are already in desperate need of recapitalisation and modernisation.

Across the military, the urgent emphasis on operations and readiness will starve the military of resources for modernisation. In recent years, the share of the defence budget spent on capital outlays has shrunk, while the share spent on pensions has grown.[59] These capital outlays are typically insufficient even to pay for committed liabilities — previously-signed contracts — risking default on existing contracts and further reducing the funds available for new acquisitions.[60] Each of the three services is allocated less money than it requests from the government, but the Navy has been particularly hard hit, receiving only 60 per cent of the funds it requests for modernisation.[61]

Across the military, the urgent emphasis on operations and readiness will starve the military of resources for modernisation.

Similarly, for the Army itself, the risk is that a renewed focus on operations on a 'hot' border will prevent its long-planned modernisation and downsizing. The current Chief of Defence Staff, General Bipin Rawat, while in his previous position as Chief of Army Staff, had sketched a plan to cut 100 000 personnel from the Army to ease the budgetary pressure of personnel and pension costs and to facilitate the Army's transition to a more technology-centred force.[62] That reform, in the context of the fresh threat on the LAC, may now also be deferred.[63] At a minimum, even if the Army's downsizing proceeds, it plans to offset its personnel reductions with greater investments in technology.[64] Either way, the Army's budget is likely to keep growing.

The crisis also revealed the urgent need for modernisation in other, non-traditional domains. At the height of the crisis, China launched multiple cyber intrusions against civilian infrastructure in India.[65] They were the latest episode in a long string of intrusions that suggest systemic vulnerabilities in India's vital cyber networks, which have largely been neglected with a paltry investment in defences.[66] In the wake of Ladakh, Chief of Defence Staff Rawat conceded that India may never close the gap with Chinese cyber capabilities, but declared that modernisation is urgently required.[67]

Alongside modernisation, the Indian military may continue to defer its maritime expansion, which it has repeatedly delayed and scaled down. Debates on the Indian Navy's force structure are often reduced to the question of whether it should acquire a third aircraft carrier, as an oversimplified proxy for debates over Indian naval strategy. In fact, the under-resourced Navy is struggling to even maintain its current modest force levels — its submarine fleet, for example, is shrinking because it cannot replace its ageing boats before they retire.[68] With declining budgets and dysfunctional procurement processes, its ships lack critical capabilities — its dedicated anti-submarine warfare corvettes, for example, lack advanced sonars and torpedoes.[69] Given its capacity constraints, the Navy has drastically scaled back its earlier expansion plans.[70] Thus, for the Indian military, maritime expansion is not a matter of crafting an ambitious new naval strategy, but simply maintaining a combat-effective force in the face of a growing Chinese Navy.

If India's maritime expansion continues to be deferred, the Navy will quickly lose the capability to deter or defeat Chinese coercion in the Indian Ocean region. The PLA Navy is rapidly expanding — from 2014 to 2018 it launched new shipping with more tonnage than the entire Indian Navy.[71] Since 2008, it has maintained a naval task group in the Gulf of Aden, and a constant presence of at least seven ships in the Indian Ocean.[72] Its new long-range and long-endurance ships are designed to wield and sustain force in distant waters such as the Indian Ocean.[73] It has built its first overseas military base in Djibouti, and is positioning itself for port access in several regional countries, including India's neighbours, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, and Burma.[74] These expanding military capabilities and footprint give China tools to coerce regional states, and operational advantages for warfighting. Its security practices and doctrinal publications have in recent decades consistently displayed an ever-increasing ambition to execute military operations in the "far seas", to include the Indian Ocean.[75] This matters for the future of Indian military in the region. If India fails to invest quickly and generously enough in its own naval capabilities, at a time when China is rapidly expanding its own military presence, it will find it more challenging to assert even temporary and local sea control to sustain naval operations, or the ability to project force across the ocean.

The sheer size and complexity of the Indian Ocean region offers China a wide menu of new options to degrade India's influence, threaten its interests, and pressure it militarily.

India may yet accelerate or at least continue its modernisation in the Indian Ocean. It has, for example, mooted a greater fortification of the Andaman and Nicobar Islands.[76] But so far, such maritime expansion has not materialised. Unlike the rebalancing of the Army's strike corps, the military has not made any costly signals of a post-Ladakh expansion in the Indian Ocean.

Deferring military investments in the Indian Ocean region will set back India's ability to compete with China. Compared to the land border, swings in the balance of military power and political influence in the Indian Ocean region are more globally consequential. At the land border, the difficult terrain and more even balance of military force means that each side could only eke out minor, strategically modest gains at best. In contrast, India has traditionally been the dominant power in the Indian Ocean region and stands to cede significant political influence and security if it fails to answer the expansion of Chinese military power. China, correspondingly, stands to gain the ability to secure its critical sea lines of communication — thereby eliminating a major strategic vulnerability — and potentially decisive leverage in its strategic competition against India.[77]

The sheer size and complexity of the Indian Ocean region offers China a wide menu of new options to degrade India's influence, threaten its interests, and pressure it militarily. For years, China has underwritten a trenchant rival in Pakistan. But more recently, it has also cultivated security partnerships in India's other neighbours, from Sri Lanka to Bangladesh to Burma.[78] China's military base in Djibouti allows it to sustain an enduring expeditionary presence in the northern Indian Ocean.[79] And its survey ship and underwater drone activity suggest it is preparing for future naval operations in the Bay of Bengal.[80] With these manifold options, China has gained an unprecedented ability to encircle India, threatening it in multiple domains and theatres simultaneously. Gaining a competitive advantage in the Indian Ocean, therefore, is the real prize — a far more strategically significant threat to Indian power than the more heavily militarised and violence-prone LAC.

Was this Beijing's plan all along? Its motivations for the crisis have been notoriously obscure. But provoking such a crisis, with its predictable effects, is certainly consistent with the PLA's view of India, as a weaker but nettlesome potential spoiler. The 2013 edition of the Science of Military Strategy — the latest version of the PLA's most authoritative strategic text — sees India as a rising power, extending its influence in all directions: "[India's] strategic deployments will be reflected more in its intentions to control the South Asian subcontinent and the Indian Ocean, and it will give more stress to paying attention to both the land and the sea."[81] India's growing power, then, would logically impede China's quest for greater access and control of the "two oceans region", encompassing the western Pacific and northern Indian Oceans — and neutralising Indian opposition to China would be a high strategic priority for Beijing.[82]

Whether or not China intended the original Ladakh incursions as a competitive-strategy ploy, it now has a foundation to use the crisis in that way.

Redoubling India's focus on its land borders would also be consistent with a "competitive strategies" approach, in which the objective is to compel the adversary into making less productive or less threatening strategic investments.[83] India's traditional focus on its continental threats, its sensitivities over defending every inch of national territory, its historical neuralgia about the shock of the 1962 war, and its struggles to modernise its military are established features of Indian strategic behaviour, and would all have been well known in Beijing. China simply had to issue a nudge — a relatively minor military action in its Ladakh incursions — to reinforce and amplify India's prior biases and activate its military-organisational instincts. The stimulus of the incursions then cascaded predictably through the machinery of the Indian government and military.

Whether or not China intended the original Ladakh incursions as a competitive-strategy ploy, it now has a foundation to use the crisis in that way. If it detects unusual circumspection from New Delhi — including, for example, moves to fortify the Andaman and Nicobar Islands — then it need only ratchet up the tension or violence on the LAC. Beijing could use further aggressiveness from the PLA — the threat of further incursions, or even the possibility of accidental conflict — to deliberately generate risk on the border, to again defer India's oceanic ambitions. Whether or not this was by design, the new strategic reality of political distrust and the increased militarisation of the LAC now provide a useful context in which any tactically minor PLA manoeuvre will be magnified, eliciting outsized strategic concerns in India. In their strategic competition, China has set the conditions for India to react in ways that suit China's ambitions.

China incurred only marginal costs

As the Ladakh crisis prolonged troop deployments on both sides, month after month, it inevitably imposed material costs on each military.[84] Some analysts claim that these costs will disproportionately fall on China, so the crisis should benefit India in the strategic competition. This may be because the PLA's deployment on the LAC will require a longer and more elaborate logistics chain than the Indian Army's — the LAC is more distant from major Chinese garrisons, and the PLA less accustomed to operating in its harsh environment.[85] Or it may be because heavier militarisation will finally make the LAC as costly for China as it long has been for India. Put another way, these arguments contend that the 'LoC-isation' of the LAC is a net positive for India, because the 'cost-exchange ratio' favours India — that is, the marginal costs of additional militarisation are greater for China than they are for India.

This may or may not be true — reliable data are scarce. It is unclear how much the Indian military has spent on the crisis — budget documents reveal in 2020 the Army and Air Force made unplanned expenditures for stores and other consumable expenses of over INR 68 billion (approximately US$908 million), and unplanned capital outlays for construction works and other equipment of over INR 141 billion (approximately US$1.88 billion).[86] This was probably mostly, though not entirely, crisis-related emergency expenditure on infrastructure for deployed forces and munitions for aircraft. These forces have, to date, occupied hurriedly constructed and austere positions; as India decides to make its enlarged deployment in Ladakh more permanent, the construction of larger and better-equipped fixed bases and their supporting transport and energy infrastructure will incur heavier costs.

There are no comparable estimates of costs on the Chinese side. Given the opacity of the Chinese system, even top-line estimates of the overall defence budget vary widely. Estimates of the PLA force levels at the LAC, usually leaked by Indian government sources, also feature suspiciously round numbers — such as 50 battalions — and are suspiciously comparable to Indian force levels.[87]

Even without reliable data, and even if the cost-exchange ratio did favour India, China is better positioned to weather the operational and strategic effects. No doubt the PLA's new deployments and supporting infrastructure have been costly. But the relative cost of this increased militarisation — its impost on the defence budget — is likely to be more manageable in China, because China's defence budget is three to four times larger than India's.[88] Over the longer term, if and when disengagement occurs, the PLA may determine it can meet its operational requirements with fewer troops than India. After the Doklam crisis, the PLA reportedly stationed one brigade near the standoff site, in Yadong.[89] Near Ladakh, it may maintain a similarly modest presence within easy reach of the LAC, confident that it could deploy forces from rear areas of Tibet if necessary because those reinforcements could use high-capacity roads and would already be acclimatised to the plateau.[90]

Image: WikiCommons/ Prime Minister's Office (GODL-India).

Operationally, the extended deployment on the LAC was probably burdensome, but not decisively so. PLA troops likely suffered difficulties maintaining high readiness — for example, they probably suffered higher rates of medical casualties caused by operating at high altitude.[91] Sustaining such large formations of troops for many months, including through a brutal winter season, would have severely tested the PLA's logistics arrangements. But for precisely that reason, it would probably have been welcomed as a field test of the PLA's recent reorganisation and its joint combat service support capabilities, and as an opportunity to rotate inexperienced troops through an operational environment.[92]

Strategically, the PLA is unlikely to shift any additional resources to its Western Theatre Command, in part because it is already ponderously large, with over 200 000 soldiers.[93] But also in part, because the relatively mild territorial threat from India is secondary to the PLA's primary concerns of US forces in the western Pacific. Thus, even if the PLA were to reinforce the LAC to a level comparable with India, such a reinforcement would have negligible impost on China's defence resources or priorities. The personnel and equipment burden could be easily absorbed by the Western Theatre Command and would not — contrary to some analyses[94] — disrupt the existing allocation of resources dedicated to China's existing priorities.

In contrast to the easily absorbed material costs, the political cost of the Ladakh crisis was probably more vexing for China. Even if China successfully imposed a fait accompli territorial revision, that gain may have come at the expense of a much more valuable, albeit rocky, overall relationship with India. Following the Ladakh incursions, India openly signalled two related political costs: that the crisis would disrupt the economic relationship with China; and that it would compel India to deepen its security relationship with the United States. In both cases, the threat of more harm to come was worse than the direct impact of Indian actions during the crisis. India has not broken off relations with China or entered into an alliance with the United States, but it signalled that it could easily move in those directions — and it was that coercive threat of yet-unrealised harm that probably motivated China.

Strategically, the PLA is unlikely to shift any additional resources to its Western Theatre Command, in part because it is already ponderously large, with over 200 000 soldiers.

Both of these threats grew significantly more pronounced after the 15 June skirmish in the Galwan Valley in which Indian soldiers were killed. Indian domestic opinion turned decisively against China — the government would henceforth face less domestic resistance to taking a harder line against China.[95] Foreign Minister Jaishankar declared that "the India–China relationship is today truly at a crossroads", implying a threat of a more comprehensive economic decoupling.[96] Early in the crisis, India had taken punitive measures against China by banning some Chinese-origin apps and tightening rules on foreign investment. Even if those measures did not in themselves impose significant costs on China, New Delhi judged that holding the future economic relationship at risk, rather than the local balance of military power, was its best source of bargaining leverage.

The corollary of India's threat to rupture the relationship with China was the threat to deepen its partnership with the United States. Soon after the June skirmish in Galwan, some analysts relished the prospect of India abandoning the fig-leaf of nonalignment and joining the US-led camp in a new Cold War against China.[97] Adding credibility to this threat, the United States reportedly provided intelligence support and emergency supplies of extreme-weather clothing to the Indian Army reinforcements on the LAC.[98] It also quickly leased India two Sea Guardian drones — designed to provide long-endurance surveillance over a wide area — which, although currently operated by the Indian Navy, may in the future be deployed over land near the LAC.[99]

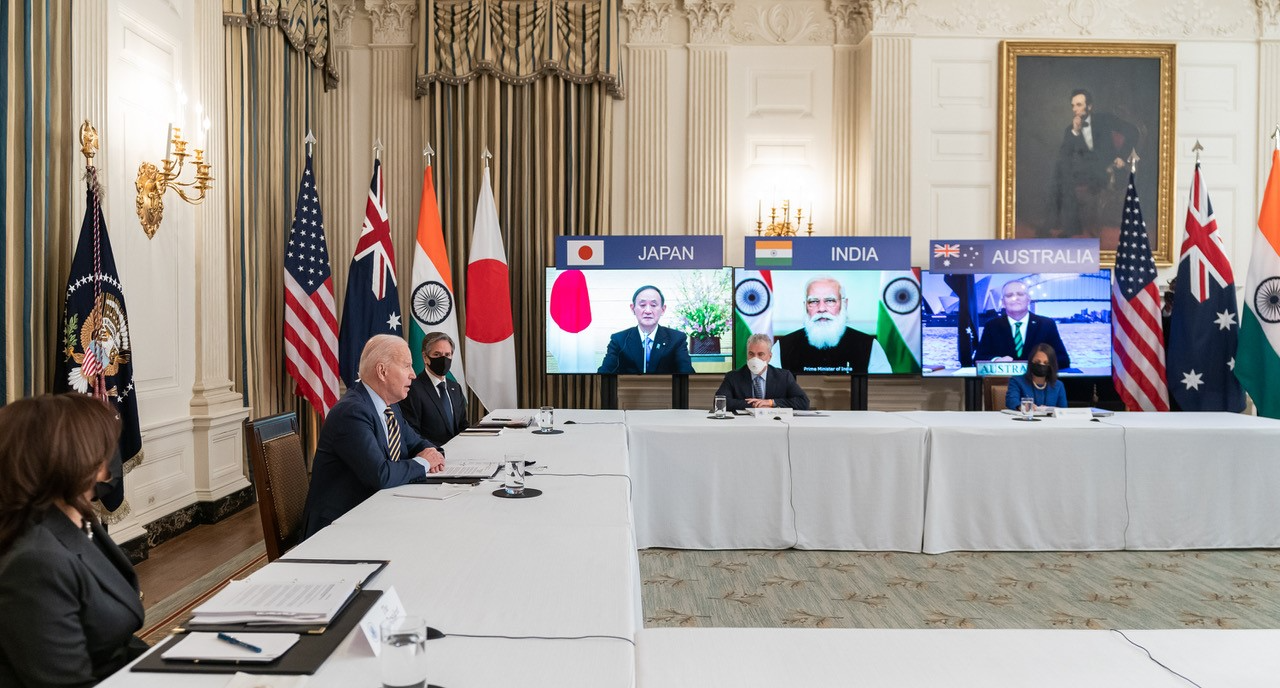

India also deepened its commitment to the quadrilateral coalition (Quad) with the United States, Japan, and Australia — it finally acceded to Australia's inclusion in the MALABAR naval exercise in November 2020, and participated in the Quad's first stand-alone ministerial-level meeting in October 2020 and its first-ever national leaders' summit in March 2021. Such advancement of the Quad partnership was very likely propelled by New Delhi's sharpened threat perceptions of China. While deepening quadrilateral cooperation was more symbolic than substantive, the notion of a coalition of capable partners has consistently irked Beijing, and New Delhi very likely intended these steps as a political signal of greater alignment to come.[100]

To some extent, China had already accounted for these political costs. According to some estimates, Beijing regards an India–US compact as a predetermined, structural reality of geopolitics, an unavoidable byproduct of China's rise, and unaffected by China's policy actions.[101] In this view, the India–US partnership may actually have enabled and emboldened India, giving it added confidence to revoke Jammu and Kashmir's autonomy and to press ahead with military infrastructure construction near the LAC.[102] If China is indeed convinced that India was already 'lost', it would calculate it had nothing further to lose from continued belligerence or future provocations.[103] Indeed, according to Chinese analyses published after the Galwan skirmish — presumably more strident as a result — Beijing's strategic elite portrayed the crisis as the product of an anti-China government in New Delhi that has bound itself to American policy. China's strategy, therefore, should be focused on subduing India — demonstrating that China is the superior power that can impose its will — as a function of China's larger strategic competition with the United States.[104]

Nor is there compelling evidence that the Ladakh crisis has diminished China in the eyes of regional states. For many Southeast Asian countries, China already looms large as an aggressor because of these countries' own territorial disputes with China in the South China Sea, and those suspicions were only reinforced by China's anger over investigations into the origins of the COVID-19 pandemic.[105] Beyond that, the Ladakh crisis is largely seen as a particular India–China problem, and regional officials have been careful to maintain a studied neutrality in public.[106]

Nevertheless, Beijing's agreement to disengage suggests the political costs did shape its calculus. China's broader strategic context likely played a critical role in its decision-making. In particular, the CCP has grown concerned over "profound changes unseen in a century"[107] — a current moment of instability accelerated by the pandemic and resulting anti-globalisation impulses. Following the deadly clash at Galwan and the Indian occupation of the Kailash Range peaks, Beijing was probably also sensitised to the risks of an unwanted war. The continuing presence of large combat formations in close contact with the adversary represented an unplanned and ongoing risk for China. In this environment, the CCP's priority is to ease external pressures that challenge China's economic development and national rejuvenation — including the formation of counterbalancing coalitions — and reduce the number of risks it faces.[108]

The first phase of the disengagement plan included the withdrawal of the Indian forces that had occupied the Kailash Range peaks, thereby expending India's only military leverage gained since the crisis began.

In that context, India's strategy of deliberately generating the risk of a broader rupture in the bilateral relationship probably took on added salience, and China had little more to gain. On the ground, the PLA was quickly satisfied with the operational gains of its incursions. As Ret Lieutenant General H S Panag, a former commander of the Indian Army's Northern Command, observed, the disengagement plan in effect recognises most of China's expansive 1959 claim lines, albeit with some provisional restrictions on patrolling and troop positions.[109] More broadly, this would also have satisfied the need to clarify the balance of power, with China imposing its will on India. Those goals achieved, China had signalled it was willing to pull back its forces as early as June 2020 in a disengagement plan that led to and was derailed by the Galwan Valley skirmish. Satisfied on the ground, and facing unrelenting pressure on multiple foreign fronts, Beijing seems to have calculated that enduring Indian enmity would serve no useful purpose.

Indeed, much of the costs that China did bear have diminished since the disengagement agreement was struck. The first phase of the disengagement plan included the withdrawal of the Indian forces that had occupied the Kailash Range peaks, thereby expending India's only military leverage gained since the crisis began. The establishment of buffer zones also reduces the risk of accidental confrontations which may have concerned Beijing. India also rolled back some of the restrictions on Chinese foreign direct investment in India, which had been imposed as a punitive threat early in the crisis.[110] These Indian military and economic concessions were important acts of assurance that signalled to China that there are benefits to resolving the crisis. For China, however, they not only reduced India's direct pressure but, perhaps more importantly, they signalled that India was at least pausing the threatened deterioration in relations. For the time being, at least, the political costs would stop accumulating and in fact greatly declined.

The costs China suffered in the crisis, therefore, were mostly political rather than material, more threatened rather than realised, and largely reduced when the disengagement plan was agreed. New Delhi's strategy of threatening a major break in bilateral relations doubtless served to sharpen the choice for Beijing, but other global pressures were necessary enabling conditions. A similar Indian policy may not work as effectively next time. And the political cost did not thwart China's objectives of asserting its LAC claims or asserting its dominant national power; it allowed India to extract a face-saving disengagement plan but did not coerce China into any concessions. As the strategic competition enters the next phase after disengagement, whatever political costs Beijing faced have been significantly diminished. It emerges from the crisis largely unscathed.

Lesson 2 Rapid Development in China and India

Source: https://www.lowyinstitute.org/publications/crisis-after-crisis-how-ladakh-will-shape-india-s-competition-china

0 Response to "Lesson 2 Rapid Development in China and India"

Post a Comment